Incorporating Generative AI in Teaching and Learning: Faculty Examples Across Disciplines

Faculty across Columbia University are reimagining their course policies, assignments, and activities to refocus on student learning and transparently communicate expectations to their students about the use of generative AI. In what follows, faculty across disciplines provide a glimpse into their approaches as they experiment with AI in their classrooms and teach AI literacy to their students.

Meghan Reading Turchioe

Meghan Reading Turchioe

Assistant Professor, Columbia University School of Nursing

In our “Research synthesis through the visualization of health data and information” course, we are hoping to increase students’ conceptual knowledge of generative artificial intelligence (AI) and use ChatGPT to develop coding capabilities. Conceptual knowledge of generative AI is important for future nurse leaders and scholars because it will be increasingly integrated into healthcare and health sciences research in the coming years. Moreover, ChatGPT may reduce the cognitive load, or processing demands imposed by a set of tasks, associated with learning programming. Prior work has demonstrated success in providing scaffolding tools to ease the cognitive load when novice students are learning to program. By providing ChatGPT as a tool while learning programming, our goal is to leverage AI to provide the cognitive scaffolding to alleviate the cognitive load associated with programming and coding, and help students engage in higher-order thinking and cognitive skills.

Hod Lipson

Hod Lipson

James and Sally Scapa Professor of Innovation at Columbia, Department of Mechanical Engineering and Data Science Inst., Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science

I encourage and credit students for using generative AI in their homework. For example, one of my classes called “Robotics Studio” involves students designing robots. Students can design the robots manually, but I encourage students to augment their concept generation using generative tools like StableDiffusion. They get extra credit if they do. I now expect more creative productivity, so students who opt to not use AI might have a harder time keeping up. Students are required to document the entire use of AI by listing the prompts used and results obtained.

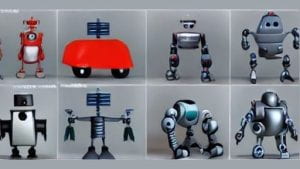

Here is an example of robot concepts proposed by the AI:

Eight robot design concepts created by StableDiffusion.

Kirkwood Adams

Kirkwood Adams

Lecturer in the Discipline, English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University

In redesigning my first-year writing class, I am developing an approach to AI literacy that teaches comprehension of machine intelligence’s capabilities.

I hope my students will learn to judiciously select only certain aspects of their thinking, reading, and writing labor to be augmented with the assistance of AI systems—if at all.

Together, we will conduct inquiries into generative AI outputs through hands-on use of AI systems. These experiential AI learning activities resist the advertised potential of such systems, billed as capable of replacing any complex task with a single keystroke.

I will teach the concept of genre more directly than previously, as machine intelligence can readily replicate genre conventions. Though ChatGPT can churn out limericks, film treatments, and essays, students need to understand that genres works beyond the formulaic & machine reproducible conventions that may define them.

Following Carolyn Miller, I hope to teach my students to understand genre, more capaciously, as a form of social action. Early in the term, students in my class will probe their own knowledge of genres, leveraging ChatGPT’s reliable showcasing of genre conventions, through a lesson that draws upon their own expertise in genres that matter to them.

Christine Holmes

Christine Holmes

Lecturer, Columbia School of Social Work

The purpose of the course “SOCWT7100 Foundations of Social Work Practice: Decolonizing Social Work” is for students to engage in critical awareness and practice of anti-Black racism, social justice, radical methods of social change and coalition building. I designed an activity for a unit on implicit bias to help students develop a deeper awareness of the social, political and ethical implications of using AI in social work. After reviewing the social work field’s Standards for Technology in Social Work Practice, students meet in small groups to analyze how the standards relate to provided case vignettes in which they would use AI tools in social work with individuals and communities. As part of the small group discussion, students generate at least one suggestion to modify or add to the Standards for Technology to uphold the tenets of anti-oppressive practice and resist anti-Black racism, while using AI. The groups’ suggestions are then collected to create a class set of standards for technology to periodically revisit and revise throughout the course as relevant case challenges are discussed.

Christopher W. Munsell

Glascock Associate Professor of Professional Practice of Real Estate Development Finance, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

with Victoria Malaney-Brown, PhD, Director of Academic Integrity

In Real Estate Finance II, a master’s-level course, students learn how to construct a joint venture waterfall. This complex, layered calculation determines how the cash flow of a commercial real estate asset, or a private equity investment, is distributed among partners. When studying complex subject matter, students often resort to external online sites to supplement their learning. In this particular course, ChatGPT is intentionally introduced and incorporated during the completion of an assignment. In preliminary testing, ChatGPT produced a mix of correct and incorrect responses. The comparison of generated responses to those by students who received traditional classroom instruction enables us to highlight the opportunities and challenges of using Large Language Models in learning financial theory. This exercise also helps inform students’ decision-making process when making real estate investments in the professional world.

Michelle Greene

Michelle Greene

Assistant Professor, Psychology, Barnard College

My approach to generative AI products is twofold: first, to motivate students to use their own creativity such that they are not incentivized to outsource the work to a machine, and second, to make the perils and possibilities of these technologies part of what we learn in the classroom. David Wiley has termed many college assignments “disposable” because they do not have a readership beyond student and professor and are quickly forgotten by each. I’ve been inspired by leaders in Open Pedagogy, such as Karen Cangialosi, who have students write for the public to create products with lasting impact and meaning. When I was at Bates College, I had students collectively write their own open textbook. Knowing that their writing would be visible to the world inspired them to bring their best selves, and they were proud to be authors on a product with a citable DOI. I plan to keep this approach at Barnard. For example, having students create zines based on class content instead of a more traditional essay. Regarding the second approach, I am lucky to teach at the intersection of cognition and AI. In my spring seminar, Modeling the Mind, students will be assigned to find cognitive tasks that are easy for humans but hard for ChatGPT. This not only shows the design principles behind this style of AI but also shows students that these tools are not human intelligence.

Mark Hansen

David and Helen Gurley Brown Professor of Journalism and Innovation; Director, David and Helen Gurley Brown Institute of Media Innovation, Columbia Graduate School of Journalism

I teach computational methods in the Journalism School. My classes draw on ideas from Statistics and Machine Learning, as well as Critical Data Studies. Students see data and computation as societal forces to report “on”

Algorithmic Accountability, Fairness in Machine Learning, Data Collection and its Gaps

as well as tools to report “with”

Identifying Patterns, Labeling Data, Structured Data from Unstructured Documents.

Generative AI tools like ChatGPT let us introduce basic ideas from Computational Thinking — like abstraction and decomposition — without invoking a formal programming language.

This played out several times during our class in the Spring of 2023. While, at one level, ChatGPT and other Large Language Models (LLMs) are effective writing aids, they have also evolved into Chat Assistants that help people with little-to-no coding experience prototype sophisticated AI systems.

We start with approaches for creating structured data from unstructured documents and webpages. In these lessons, for example, web scraping is introduced first as a translation problem (from HTML to JSON, say), and then as an opportunity for AI-based code generation (the LLM writing a Python program that can be run to pull data from a web page). In the first case, the AI is performing a black box calculation, while in the second it is programming, offering students a chance to evaluate the code before running it. (Underscoring the need for students to understand the code in the first place!)

In example after example, students use LLMs to work with text and code and data in new and exciting ways. But the complexity of these technical platforms — the “extractive” nature of their instantiation, their capacity to produce confabulations — deepening our lessons in Computational Thinking, specifically examining different technical workflows and assessing the veracity of our AI-based applications of data and computation.

Ioana Literat

Ioana Literat

Associate Professor of Communication, Media and Learning Technologies Design, Teachers College

In redesigning my courses, I started with an “assignment audit” to determine which of my course elements were relatively AI-proof, and which needed to change in the post-ChatGPT era.

I decided to keep two of my course requirements unchanged: social annotation on Perusall (which requires close reading and very specific engagement with the material and peers) and, respectively, the final research papers (which are scaffolded and require original data collection and analysis).

The rest of the assignments needed a significant revamp. For instance, I replaced my midterm reflection paper—which focused on a theoretical topic and was broad enough to be generated by AI—with an oral presentation on the students’ research process and preliminary findings. I also rethought the weekly reflection questions for each content unit, to make them more specific and more applied. Rather than eliciting general, boilerplate reactions, the new questions required students to apply concepts to recent examples; reflect on their personal experience; use creativity, imagination and role-play; identify specific examples or passages from the readings; and respond in ways other than text (e.g. by creating a meme or a brief video).

This is not to say that generative AI tools like ChatGPT were discouraged in the course. The AI policy included in my syllabus only prohibited the use of AI for drafting writing assignments, but all other uses were explicitly permitted (e.g. using AI tools to find background information about a topic, clarify challenging material, draft outlines, or improve grammar and style).

Erik Voss

Erik Voss

Assistant Professor of Applied Linguistics & TESOL, Arts & Humanities, Teachers College

Artificial intelligence that combines text generation tools with training as a chatbot (e.g., ChatGPT) have posed ethical challenges but also offer pedagogical benefits for students. I see potential in the use of such a tool in the role of an assistant in my computational linguistics course at Teachers College. For example, one of the most challenging aspects for students in this course is learning the Python programming language at the same time they are grasping how natural language processing concepts can facilitate analysis of language. A tool such as ChatGPT has the potential to support students’ learning and debugging Python code. This approach is in line with how coding is now taught in the Introduction to programming course at Harvard.

In order to implement this approach successfully, my syllabus will now include a lesson on how to use generative AI ethically and responsibly. In addition, I believe it is essential to focus on the development of critical thinking skills and the evaluation of generated text. Although use of these tools is now part of the course, it is important to include in the syllabus that submitting academic work that has been entirely generated by generative artificial intelligence tools is unacceptable.

Aparna S. Balasundaram

Lecturer, Columbia School of Social Work

The purpose of the course “SOCW T660A Human Behavior and the Social Environment” is to engage student’s “sociological imagination” about human behavior, deepening understanding of the impact of the environment on the individual at various stages of the human life course.

During week 3, we explore the influence of macrosystems in the context of environmental and climate justice. One focus area will be the impact of gentrification. I plan to use AI tools as part of the breakout activity during this class.

The activity is called, “Which Lens Matters? World View Vs. Social Work View.” Students will be first asked to use ChatGPT to generate a response to a social problem that most of the world would agree has no merit, like domestic abuse. We would then generate a response to our class topic, gentrification. The questions asked in ChatGPT will be ‘‘What are the pros of domestic violence” and the AI generated response clearly states, “there is none.” However, the response to the next question, “What are the pros of gentrification” currently generates potential pros, which reflects a dominant world view that speaks to inherent systemic biases. The breakout room group discussion activity will be based on this reality and its implications for social work practice.

Alexander Cooley

Claire Tow Professor of Political Science, Barnard College

I’ve developed an assignment using ChatGPT for my upcoming “Transitional Kleptocracy” class in the Fall. The pedagogical justification for the assignment is as follows.

This assignment uses ChatGPT to explore how wealthy/politically influential individuals with controversial pasts (corruption scandals or political controversies) actively manage their global public profiles. The assignment asks students to use ChatGPT to write two profiles: a positive profile (in the style of a public relations firm) and a more critical profile (in the style of a human rights or anti-corruption watchdog) of a given individual with a controversial history (some may even have been sanctioned).

The first part of the assignment invites students, using some preliminary research, to develop detailed prompts to construct these contrasting profiles.

The second part of the assignment (without ChatGPT) invites the students to critically assess the relative strengths of the two profiles they have just generated. It is likely (though not certain) that the more positive profile will be the most convincing, as the publicly available information that ChatGPT has gathered will be more sanitized and plentiful than the controversial information, which tends to be deleted or sanitized (usually by reputation management firms) from public sources such as “Wikipedia.”

The goal of the assignment is to have the students use ChatGPT in these different roles and then probe the reasons why one role may be more effective than the other.

Katherine A. Segal

Adjunct Faculty, Columbia School of Social Work

In Social Work T7320 – Adult Psychopathology and Pathways to Wellness, we have two papers used to apply the knowledge and skills learned in the course to a client of the student’s choosing. As such, both papers – the Biopsychosocial Assessment and the Treatment Plan – require a lot of personal information shared by the client, information that should not be entered into ChatGPT or other AI databases.

However, I also want to teach and encourage students to ethically utilize AI tools in their student and future professional work. To that end, I looked through the assignment description of the treatment plan paper for elements that could be drafted by ChatGPT without needing to enter much client-specific information.

I experimented with ChatGPT to identify prompts that could be used on the assignment. Specifically, I identified prompts that would help in the creation of SMART goals based on generic client information. I then shared my findings with the students as part of their preparation to write the paper. I walked the students through prompting ChatGPT to create the treatment goals using only a few client details. As this approach resulted in drafting goals that may or may not be relevant to the client (since ChatGPT wasn’t provided all of the relevant details) I then demonstrated how to take the AI-generated statements and transform them into goals that are tailored to their clients.

Moving forward, I will continue to look for elements of assignments that could benefit from AI-generated drafts and stress the importance of not entering client information into such systems.

Related resources

ChatGPT and Other Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Classroom. Digital Futures Institute, Teachers College.

Considerations for AI Tools in the Classroom. Columbia University Center for Teaching and Learning.

Generative AI & the College Classroom. Center for Engaged Pedagogy, Barnard.

Integrating Generative AI in Teaching and Learning. Faculty approaches across Barnard. Center for Engaged Pedagogy, Barnard.

Learner Perspectives on AI Tools: Digital Literacy, Academic Integrity, and Student Engagement. Students as Pedagogical Partners. Columbia University Center for Teaching and Learning.

Thinking About Assessment in the Time of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Digital Futures Institute, Teachers College.

This resource was developed by the Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning in collaboration with the Digital Futures Institute at Teachers College and the Center for Engaged Pedagogy at Barnard.